|

| Nurse of the 93rd Evacuation Hospital arrive at their hospital site at Paestum, Italy, in September 1943 after the HMHS Newfoundland was bombed (Monahan and Neidel-Greenlee, 196) |

Working 12-24 hour shifts, nurses often encountered injuries and trauma far more severe and extreme, and in larger volumes, than anything they saw in civilian practice. They also did the work while often lacking sufficient supplies, even things as basic as well-fitting field uniforms. Many wore oversized coveralls and shoes (unsurprisingly, the army was lacking in smaller sizes), as the standard white nurses uniform was essentially useless in combat situations.

Operation Shingle paints what is perhaps the most illustrative picture of the dangers nurses faced during the War. Operation Shingle was an effort critical to the fall of fascist Italy, taking place in June of 1944 and marking the start of the prolonged Battle of Anzio. Here, on this small Italian beachhead, the Allied forces set up a hospital, but the lack of real estate meant that it was surrounded by artillery battery, a gasoline dump, an airstrip, and a radar site — all legitimate military targets for the German forces when they were playing by the rules, so nurses performing lifesaving measures from this site often did so through sustained shelling. The hospital was eventually relocated to a site deemed safer, but it too became a target of deliberate enemy fire, earning the locale the very apt nickname, “Hell’s Half-Acre.” Eventually the hospital was “dug-in” to protect it from attacks and the nurses had foxholes dug under their cots, but such safety measures, as one might imagine, were superficial, and nurses, like the soldiers they treated, regularly succumbed to enemy fire. As noted in And If I Perish , “no other hospitals in World War II took more bombings and shellings, or suffered as many injuries and deaths within their staffs of doctors, nurses, and enlisted men, as well as re-injuries of patients, than the hospitals on the Anzio beachhead.” (Monahan and Neidel-Greenlee, 257)

|

| Lt. Claudine “Speedy” Glidewell, 1943 (Monahan and Neidel-Greenlee, 127) |

Working on the frontlines, many of these brave women performed their vital duties with grit, resolve, and without much fanfare, and even today their efforts are often overlooked by those with hindsight. But there are numerous stories worth highlighting.

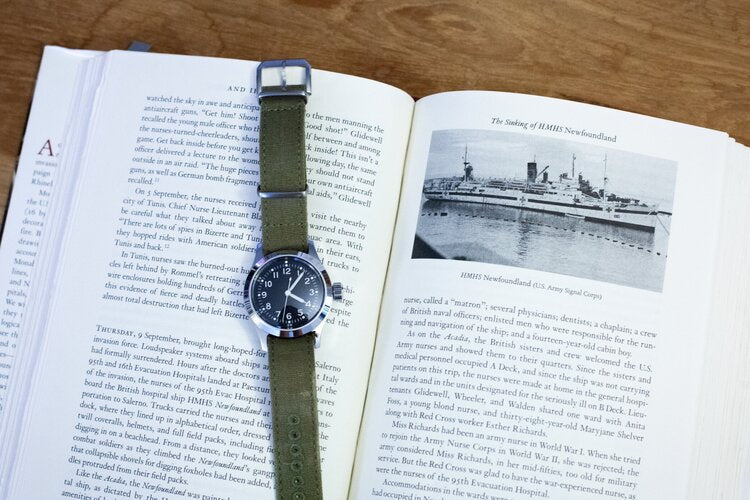

Among them is the story of Lt. Claudine "Speedy" Glidewell. Wounded when her hospital ship was intentionally sunk by the Germans she lied about the severity of her wound in order to return to duty. She served at Anzio and was awarded a Purple Heart for her wound from the hospital ship attack.

Then there’s Lt. Ruth Haskell, who sustained a back injury when she was thrown from her bunk during rough seas. She continued to work for three months with the injury, doing so out of a sense of commitment to her unit before she was eventually evacuated when her back injury became debilitating. There are similar stories from the front of soldiers going AWOL from hospitals to rejoin their units rather than risk re-assignment.

Their frontline service was recognized in the form of battle stars for their participation in the North African and European theaters. Four nurses at Anzio were awarded Silver Stars for "Gallantry in the face of enemy action", one posthumously. By the war's end 565 women had earned the Bronze Star and nurses were awarded 1,619 commendations, medals, and citations.